Victory Theater Project

Back to Architecture & Installations

An innovative theatrical environment for Mac Wellman’s site-specific play, Crowbar, transforming the historic Victory Theater into the focus of a haunting dramatic experience.

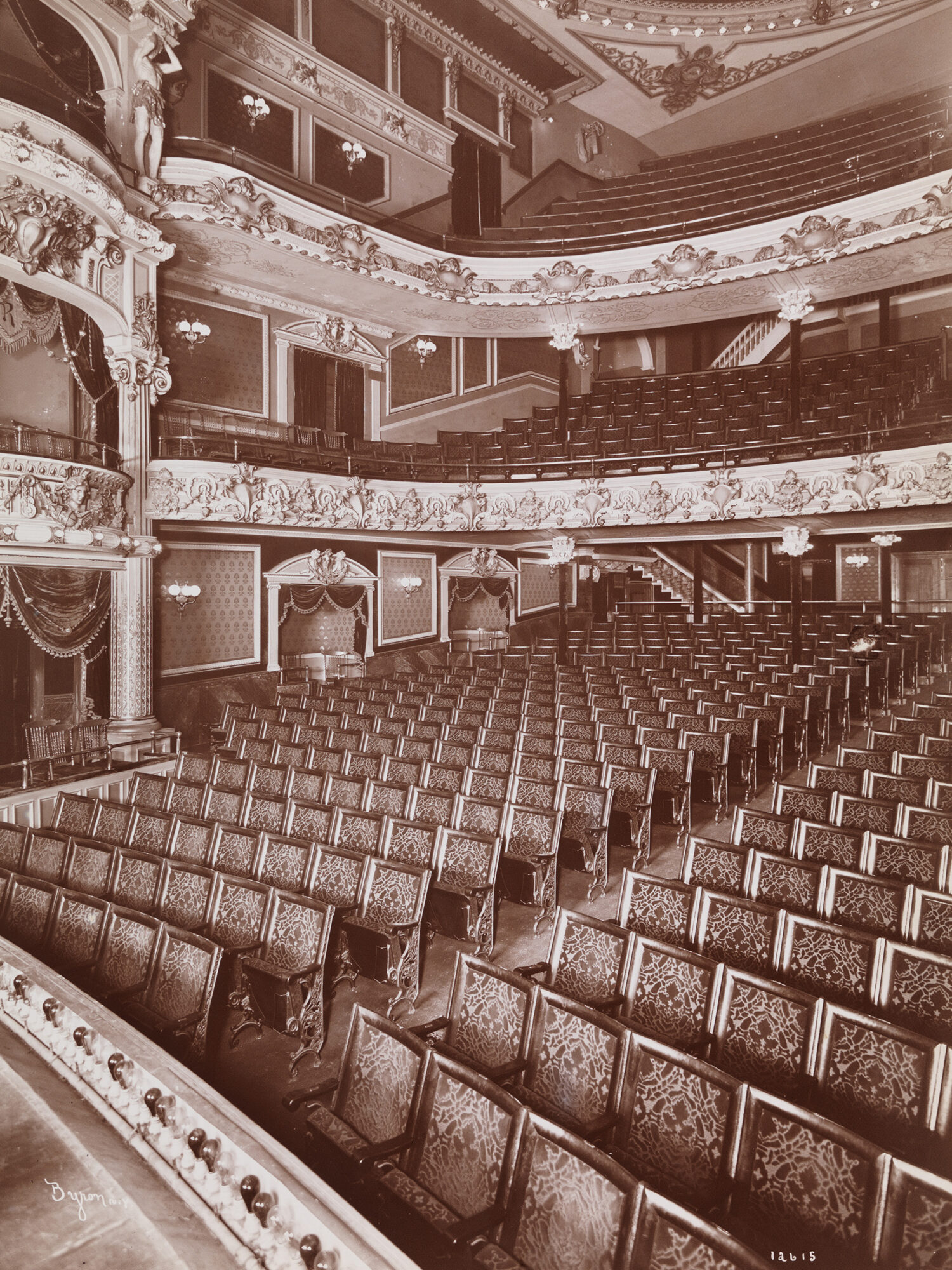

For the site-specific theater group En Garde Arts’ production of Crowbar, an Obie Award-winning 1990 play by Mac Wellman, James Sanders created an environment that turned the historic Victory Theater into the focus and frame of the performance. Inspired by the classic Hollywood “backstage” musicals he explored in his book Celluloid Skyline, he created platforms that placed the audience at right angles to the proscenium, transforming the entire ornate yet crumbling playhouse—stage, wings, flies, orchestra, boxes, and balconies—into a ghostly theatrical environment in which to play out the theme of Wellman’s history-inflected drama: that “all theaters are haunted.”

Mel Gussow, New York Times

Anne Hamburger, En Garde Arts

#Mythic Places

#Design Across Time

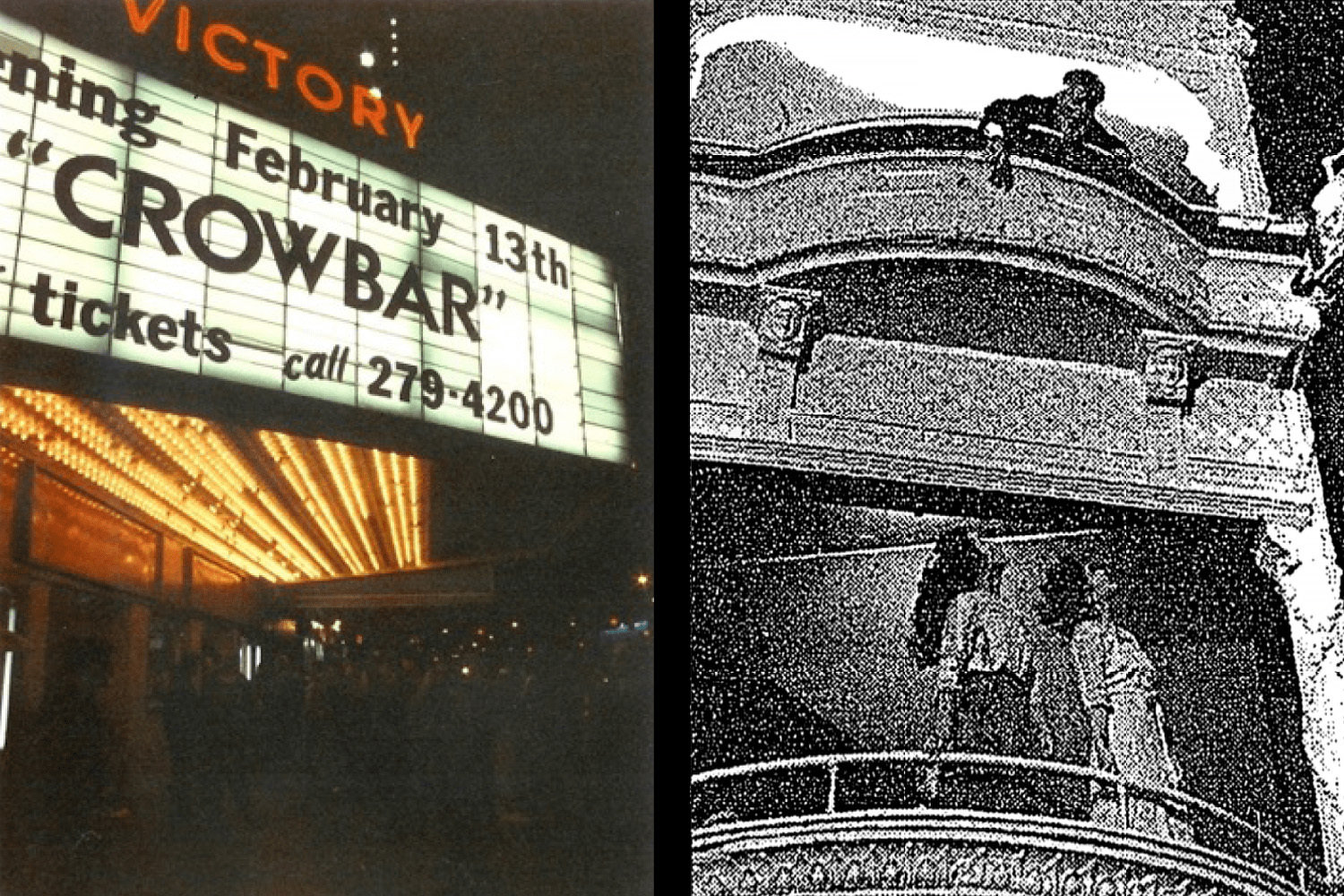

To amplify the themes of Wellman’s play—a “conjuring act,” James F. Schlatter observes, in which “past and present collide…and figures from America’s past, some anonymous and some famous, rise up to haunt the cavernous theater”—Sanders devised an innovative seating installation (above, left). Inspired by the Hollywood “backstage” musicals of the 1930s, which roamed every corner, front to back, of mythical Broadway theaters—he turned the audience sideways to view the entire interior in "cross-section": from the backstage wall, across the stage and proscenium, to the domed ceiling (above, right), orchestra and boxes, and onto the upper balconies. To immerse the audience further in the liminal “space” between past and present, he produced a four-minute montage sequence (with music by David van Tieghem) mixing 1990s and 1900s images of the theater and its 42nd Street setting, projected onto a large suspended screen (below).

“The luminous projections appear and disappear like ghosts,” Rebecca M. Groves has written, “visually haunting the interior of the same walls that they represent in order that they may resurface in consciousness at a later point in time.” Helping to further blur lines of time and space, the projected presentation also sketched the story of the Victory itself: built by Oscar Hammerstein I as the Republic in 1900, then transformed from 1902 to 1910 by producer David Belasco into the working laboratory of his great project to modernize American drama, then descending into a long twilight as Minsky’s Burlesque in the 1930s, a 42nd Street grindhouse in the 1950s, and an X-rated movie house after 1972. Restored by Crowbar to legitimate theater for the first time in sixty years, the structure would be reborn a few years later as a children’s theater, the “New Victory.”